The cost of our connected world: how to overcome challenges without downgrading technical capabilities

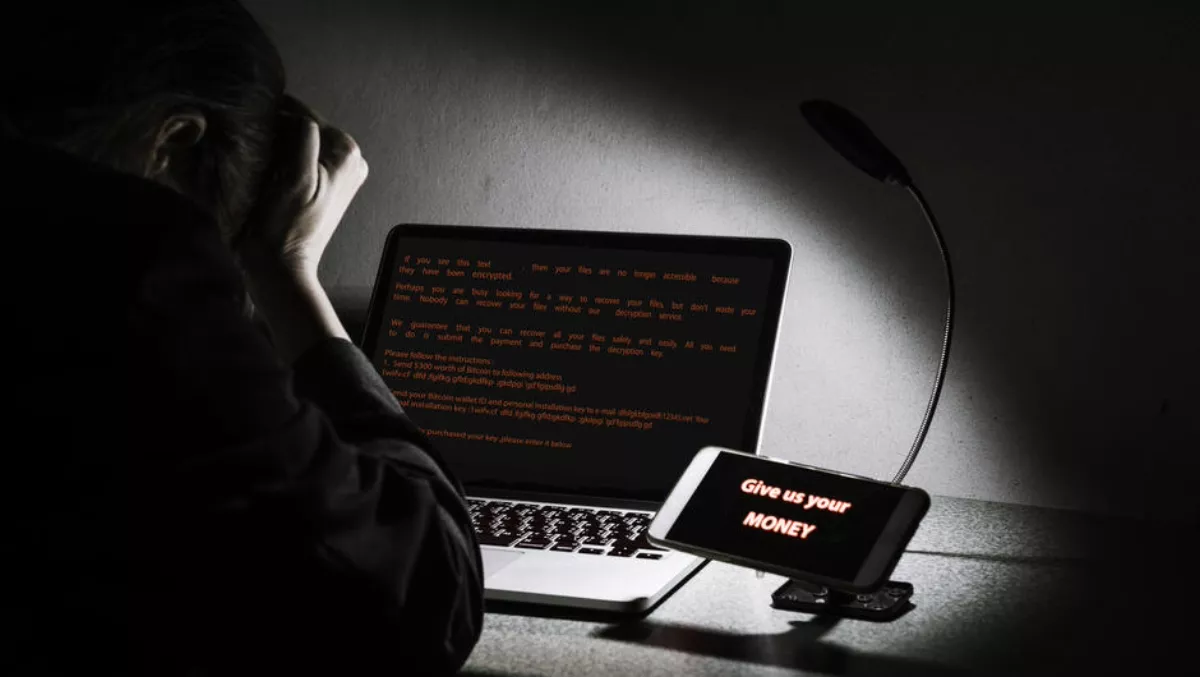

Many of the recent cybersecurity incidents have been high-profile cases that impacted millions of users worldwide and delivered a significant financial blow to many organisations.

Two attacks that stood out most in the last year were the widespread ransomware-like outbreaks, WannaCryptor (aka WannaCry, WCrypt) and Diskcoder.C (aka Petya,NotPetya). The worm-like capabilities of these threats meant that thousands of endpoints and servers around the globe were attacked at a scale and speed that had not been seen for a decade or more.

Furthermore, these ransomware attacks generated significant concern about security issues among a very broad audience.

Technological advances and their accelerated use have led to a number of scenarios, which were previously considered unlikely, becoming possible.

This has become more evident as security threats can be traced back to systems and protocols businesses use daily, which were designed without taking into account the prospect of widespread internet connectivity. This is why organisations need to think about how they can solve this paradox without downgrading technical capabilities.

Holding data to ransom is an easy way for an attacker to make a dishonest profit and seems to be on the rise. Many organisations are prepared to spend large sums in ransom payments to get their data back, even though this encourages cybercriminals to attack the same target repeatedly.

Before paying, organisations should check with their security vendor in case recovery is possible without paying the ransom. They should also check that paying the ransom will actually result in recovery for that particular ransomware variant, which was not the case for either WannaCryptor or Diskcoder.C.

Protecting data proactively is safer than relying on the competence and good faith of an opportunistic cybercriminal, and is absolutely critical for recovering from other kinds of data disasters such as fire, flood and device loss or theft. It's important to back up everything that matters to the business and keep some backups offline so they aren't exposed to corruption by ransomware and other malware.

Cyberthreats to critical infrastructure are also increasing. The malicious code in the malware Industroyer let hackers penetrate the control networks of electricity distributors and briefly disrupt the electricity supply in Ukraine.

The industrial equipment that Industroyer targeted is widely used well beyond Ukraine, including the UK, Europe, US, and Australia. Many critical infrastructure organisations are working hard to secure devices for the future. However, the ability to carry out cyberattacks on the power grid will persist unless better pre-emptive measures are more thoroughly adopted.

Organisations need to look at measures such as system upgrades, early detection of network probing, dramatic improvement in phishing detection, and more stringent network segmentation, all to help prevent and combat future attacks.

Evidence to date strongly suggests that we also can't rely solely on technology for something as significant as the electoral process. Governments must consider hybrid systems with both paper and electronic ballot records to ensure there are audit trails.

So-called hacktivism, which can change public opinion on social media, has also become the new frontier of the political stage and is used by political campaigns to reach large numbers of people. These networks have also been used to undermine electoral campaigns by spreading falsehoods, and promoting fake news reports, and conducting widespread attacks on the reputation of public figures.

Governments must ensure that users interact with technology as safely as possible by implementing national cybersecurity programs and educating public officers, such as court authorities or electoral commission officials, in cybersecurity protocols to help them make the most suitable choices.

Data is driving the next revolution in technology and AI systems. While the majority of end users understand they are giving their data to social networks or organisations through forms and applications, there are many other providers and services whose data-collecting may not be so transparent.

Privacy is a fundamental human right. The modern definition of privacy inclines towards data privacy or information privacy. This deviation makes maintaining the desired data-neutral position for the end user increasingly complex.

On one hand, there are extremely technology-driven privacy enthusiasts trying to leave no digital footprint anywhere. On the other, the vast majority of us leave digital footprints everywhere, giving cybercriminals a webscape full of sensitive data.

To maintain our desired level of privacy, we need to understand how the online businesses and services we use make their money. For example, a mobile game may show advertisements or upsell levels of the game.

If it's not obvious how the company makes money, then it is highly likely that it's doing so by selling data about us and, therefore, some of our privacy.

Generally, the most successful threats are the simplest. They're usually distributed through malicious attacks using spam, phishing, and direct download campaigns that could be mitigated just by increasing cyber-awareness among end users.

The problem is that the resources needed to make the public more cyber-aware have yet to be allocated. It's time for us to understand that cybersecurity not only depends on the providers we choose to safeguard our online activities, but also on our own behaviour. There is still a lot more work to be done.